Even the most harmless-looking child can grow into something unrecognizable when early life is shaped by instability, neglect, and violence. Few stories illustrate that transformation more starkly than the one behind the notorious name that still echoes through true crime history: Charles Manson.

He was born on November 12, 1934, in Cincinnati, Ohio, to a 16-year-old mother. From the beginning, his world was fractured. His father, described as a con artist, disappeared before he was even born. The absence wasn’t just emotional—it created a vacuum where responsibility, safety, and routine should have been.

By the time he was four, his life took another sharp turn. After his mother, Kathleen, was arrested for assault and robbery, he was sent to live with an aunt and uncle in McMechen, West Virginia. The crime, committed alongside her brother Luther, was brutal in its simplicity: a bottle smashed over a man’s head, a car stolen, and two lives diverted into prison sentences. Luther received ten years, while Kathleen was sentenced to five but served three.

Kathleen’s visits were reportedly mandatory while her son stayed with relatives, though he often resisted them. When she was released and returned home, those first weeks were later described as some of the happiest of his childhood—brief stability, a sense of being wanted, the illusion of a fresh start. But it didn’t last. Alcoholism took hold, and the household slid back into disorder. She would vanish for days at a time, leaving him to a revolving door of babysitters and temporary arrangements that offered little supervision and even less emotional security.

When his behavior became too difficult to manage, reform school became the answer—at least on paper. In reality, it failed to contain him. By nine, he would later claim he had already set one of his schools on fire. Truancy and petty theft followed, and the pattern of defiance hardened into something more entrenched.

At thirteen, he was sent to the Gibault School for Boys in Terre Haute, Indiana, a Catholic institution run by strict priests. Accounts describe harsh discipline and beatings for minor infractions. He ran away—first back to his mother, who sent him straight back, and then farther, to Indianapolis. There, the choices narrowed: steal or go hungry, find shelter wherever the night didn’t swallow you. He slept outdoors, under bridges, and wherever he could disappear long enough to survive.

Arrests came quickly, as did transfers through juvenile institutions. At one school in Omaha, Nebraska, he and another boy stole a car within days and went on a spree of armed robberies while trying to reach a relative’s home—less a random outburst than an early “apprenticeship” in crime. He even developed a tactic he later called the “insane game,” performing exaggerated shrieking, contorted expressions, and wild movements to convince potential attackers he was too unpredictable to challenge.

There were brief attempts at ordinary life. At one point he worked as a Western Union messenger, a job that suggested the possibility of something stable. But stability didn’t hold. He slipped back into criminal behavior, and the escalation became harder to ignore. Psychiatric evaluations later described him as “aggressively anti-social,” and his record increasingly reflected manipulation, exploitation, and violence.

While incarcerated, his conduct remained severe. He was arrested for sexually assaulting another boy at knifepoint in a federal reformatory. Repeated incidents and alleged sexual coercion contributed to transfers into higher-security facilities. By twenty-one, when he was released, the groundwork was set for the pattern that would define his adult life: theft, deception, control, and a relentless need to dominate the people around him.

As an adult, he demonstrated an unsettling ability to draw vulnerable people into his orbit. He married, crossed state lines in stolen cars, and drifted through criminal enterprises. His fixation on control extended to women, including attempts to establish prostitution rings and relationships with underage girls—behavior that repeatedly led him back to prison.

During a sentence at McNeil Island in Washington, he reportedly experimented with hypnosis and practiced persuasive techniques on fellow inmates, including actor Danny Trejo. Those skills—part charm, part intimidation, part psychological pressure—would later become central to what the public came to know as the Manson Family.

By the late 1960s, his worldview had fractured into a delusional ideology. He convinced followers he was a prophetic figure and claimed the Beatles were speaking directly to him through their music. From that obsession grew the “Helter Skelter” narrative: a race war he believed was imminent, followed by his rise to dominance after hiding in a desert bunker.

Before the murders that would cement his infamy, he chased music fame in the West Coast scene and briefly intersected with celebrity circles, including Dennis Wilson of The Beach Boys. But rejection, humiliation, and resentment appeared to deepen his obsession—and the obsession turned toward violence.

In August 1969, members of his cult carried out the brutal murders of actress Sharon Tate, her unborn child, and four others. The next night, Leno and Rosemary LaBianca were killed as well. In court and in public memory, the horror wasn’t only the violence—it was the sense that it had been manufactured by influence, ideology, and fear.

Prosecutor Vincent Bugliosi later framed Manson’s grip over his followers with chilling clarity:

“The very name Manson has become a metaphor for evil—and evil has its allure,”

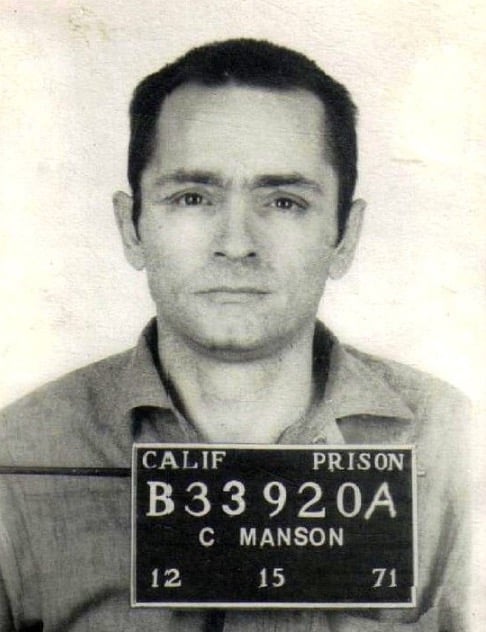

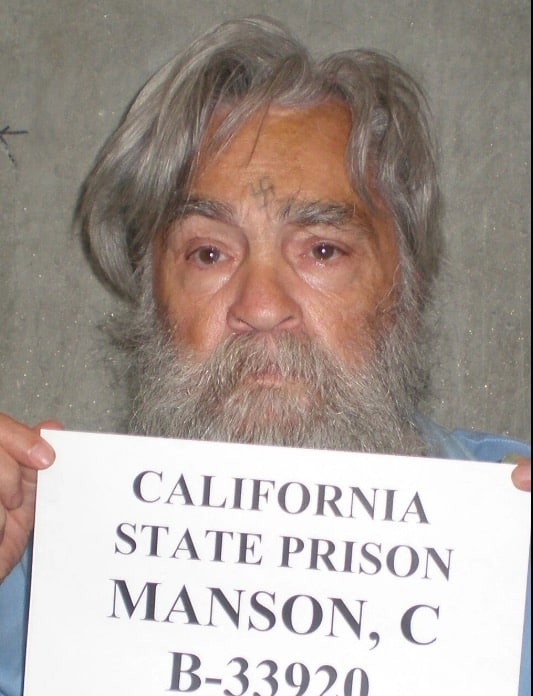

Convicted of multiple murders, including those connected to Tate, the LaBiancas, Gary Hinman, and Donald Shea, Manson was sentenced to death in 1971. His punishment was later commuted to life imprisonment after California abolished the death penalty. He applied for parole multiple times, but remained incarcerated until his death in 2017 at age 83, following cardiac arrest complicated by colon cancer.

Even after his death, Charles Manson’s legacy lingered through documentaries, books, interviews, and pop culture references—an ongoing, uneasy reminder of how manipulation can become a weapon, and how a childhood marked by chaos can intersect with choices that produce lasting harm.

0 Comments